Please visit our YouTube channel to watch Rev. Ann Marie’s video recording of this reflection.

We need a transformation of our current culture such that we can handle conflict, violence, and harm in more effective ways. The important questions are: What can accountability and consequences look like beyond courts and prisons? How can we provide satisfactory experiences for those who were harmed? How can justice truly be served?

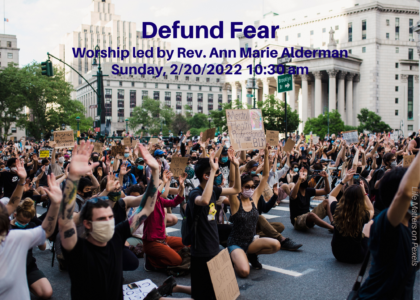

From Defund Fear: Safety Without Policing, Prisons and Punishment, by Zach Norris (Beacon Press, 2021)

Punishment teaches that those who have the power can force others to do what they want them to. Punishment involves control over someone, by fear of coercion, denying their fundamental dignity and rights. It is done to someone. Accountability, by contract, occurs with someone. Even if someone makes a mistake, that person is still worthy of basic respect and humane treatment….

Let me start by saying how much I wish the saying “defund the police” was instead the title of the UUA’s Common Read for the 2021/22 year, Defund Fear. I didn’t want to read this book. I don’t want to hear any more about whether or not we should defund the police. And I didn’t want to have to think about how awfully human beings have treated other human beings, again.

But I am so glad I read this book. And I hope you do if you haven’t yet. There is pain in this book, story after story of lives lost, but more importantly there is so much hope in this book. So much of what can be done to heal this broken world.

The author is Zach Norris. The book is subtitled Safety Without Policing, Prisons and Punishment. The author grew up in Oakland, went to Harvard, studied law, and now works as a community organizer. His book is simply amazing. It’s because he envisions a compassionate future that promises greater safety for everyone, especially for those who are most vulnerable in the present day.

He tells stories of individuals and their mistreatment and calls us all to stop the criminalization; stop labeling people as bad. Instead, treat each and every one as if they are worthy simply because they are a human being. His is such a UU vision of what the beloved community could be like, if only we didn’t hide from the stories of lives that have no measure of safety, of dignity, no avenue for healing.

It is so clear that America’s criminal justice system is based on retribution, on the primitive notion of an eye for an eye. Van Jones, in the forward, reminds us that Gandhi said, “[the notion of an eye for an eye] … leaves the whole world blind.” All the damages done, piled one on top of the other, will never add up to justice and healing. Retribution will never, ever bring justice or healing.

We must leave the us vs. them mentality behind. All human beings are worthy of safety and dignity.

No one should be defined by the worst thing they’ve ever done.

Norris presents his case over and over beginning with his own story of when his home was broken into. His two young daughters could have easily been asleep in their room when someone smashed the window trying to get in to steal something of value. The whole scary incident eventually caused Norris to change his mind and stop thinking that safety is all about bad persons who do bad things, who must be locked up, removed, punished.

Instead, he did what I truly wish all UUs would—begin to see that retribution won’t fix anything. A system built on fear isn’t the way. He began to look at who is truly benefiting from the system of criminalization.

It is clear that none of us are. None of us are “safer” now, because the system of criminalization isn’t designed to fix what is really wrong.

He says, “Believe me, I understand the desire to keep your home and family safe. I want my family to be as safe as you do. But safe from whom and from what? Are they people in faraway lands, in the ‘inner cities,’ or people right next door? Are they people you know, from within your country, your community, or even within your family? And what really constitutes the worst threat to your family? Is it really crime? Or is it facing eviction because you can’t make rent? Is it frequent hospital visits because you live near an oil refinery and your child has asthma, or because the water you drink is no longer safe? These daily realities are sometimes described as “cultural, political, and socioeconomic dynamics.” But they are as real as your heartbeat. Decades of funneling money toward a punishment dragnet, instead of investing in a real social safety net, means that one lost job, one healthcare crisis, one traffic stop can be the end of a secure life.”

He sums up the premise of this book when by saying, “When we allow the architects of anxiety to distract us from the real threats, we decrease our societal capacity to hold them—and their policies and institutions—accountable for the things than actually threaten and harm us.” He makes the case over and over that it is sexism, capitalism, racism that cause the seemingly never-ending cycle of harms. No amount of locking people up will change those systemic evils.

Yet, many of us who know about dismantling these evil systems still act as if we trust the “fear- based” model of retribution which allows us to go on believing that if we just locked up all the criminals, we would be free of crime. And we keep trying to do just that. There are seven million adults in America in jail, prison, on parole, or on probation. Norris describes how the criminal “justice” system is built on a framework of fear. The framework it employs is 1) systemic deprivation, 2) extensive and expensive systemic suspicion, 3) cruel punishment and 4) often-permanent isolation from the rest of society.

All the while, study after study shows trauma is the chief cause of violence. Why would anyone think that causing more trauma will stop the root cause of violence?

The fear-based model of safety creates more harm than it prevents, with a never-ending cycle of repeated trauma.

What can be done to end what clearly is not working?

Shifting the focus away from individual criminals to what actually causes the most suffering, Norris suggests a care-based approach that replaces deprivation, suspicion, punishment, and isolation with resources, relationships, accountability, and participation—in other words, a culture of care.

The matters raised in Defund Fear invite us to respond to public safety in the US today through a lens of faith, particularly our UU faith. When you read this book, you may likely ask yourself, as Norris did, the big, tough questions about who we are and the meaning and purposes of our lives.

Perhaps your mind and heart will change, as you journey with Norris as he illuminates and examines society’s “punish first” public safety practices and hear for yourself the traumatic and dehumanizing experiences of individuals who have been criminalized.

Our values call us to approach this book with humility, and with an appreciation for the tellers’ generosity and purpose. Every one of us has a place in the stories Norris offers. Reading this book will cause you to bring a sharpened self-awareness about your place in your community and in the world.

When I first arrived here as your developmental minister, I was invited to attend the community course on racism sessions. I think the first one I attended included folks from the Meta Theatre group I had already been exposed to while serving the Plainfield UU congregation. It included a number of previously incarcerated women I was not familiar with. There were four or five women there that night (pre-pandemic) who had served time together at the Edna Mahon Correctional Facility. One of those women talked about FORTE house, a place in Newark where previously incarcerated women could live after being released from prison. All of them spoke of the group All of Us or None, which is a support group for recently released women that gives them support and encouragement, so they don’t return to the criminal justice system

One of those women, Tia Ryans, whom I have followed on social media ever since then, has just been appointed by the Governor to the Advisory Board for the Edna Mahon Correctional Facility. This is a first; the first time a previously incarcerated woman at the same institution has been appointed to serve on the Board of Directors. For your care, for your growth, and for the care and growth of others in your community with whom you will discuss Defund Fear, it is strongly recommended that you enter this book with these questions by your side:

- What is my connection to the stories told and the harms named? Where am I in these stories? In what ways have harsh punishment benefited or harmed my community?

- What is my story of public safety? In what ways has “fear” shaped my assumptions and experiences about public safety?

- What is my complicity? What shape does—or could—my accountability take?

If you appreciated this reflection, please text to give or visit our Give Now page to support the UUCSH Share the Plate efforts to assist those in need.